White House Wants $400B to Pay for Long-Term Care

- Written by Terry Turner

Terry Turner

Senior Financial Writer and Financial Wellness Facilitator

Terry Turner has more than 35 years of journalism experience, including covering benefits, spending and congressional action on federal programs such as Social Security and Medicare. He is a Certified Financial Wellness Facilitator through the National Wellness Institute and the Foundation for Financial Wellness and a member of the Association for Financial Counseling & Planning Education (AFCPE®).

Read More- Edited By

Lee Williams

Lee Williams

Senior Financial Editor

Lee Williams is a professional writer, editor and content strategist with 10 years of professional experience working for global and nationally recognized brands. He has contributed to Forbes, The Huffington Post, SUCCESS Magazine, AskMen.com, Electric Literature and The Wall Street Journal. His career also includes ghostwriting for Fortune 500 CEOs and published authors.

Read More- Published: July 7, 2021

- 5 min read time

- This page features 11 Cited Research Articles

- Edited By

Medicare doesn’t cover long-term care — such as nursing home or assisted living care — but the Biden administration wants $400 billion over eight years to help older Americans pay for it.

The White House plan would pump more money into Medicaid with the aim of addressing a rising tide of Baby Boomers aging into the need for nursing home or assisted living care. It also comes as the COVID-19 pandemic has left long-term care facilities reeling from skilled labor shortages.

Medicare has never covered long-term care costs. When Congress created Medicare in the 1960s, it realized that the cost of paying for long-term care as the Baby Boom generation aged into it could overwhelm Medicare.

Instead, Congress decided Medicaid should provide a long-term care safety net. The idea was that Medicaid could absorb the costs because fewer people would be enrolled in Medicaid than in Medicare.

But now, Medicaid itself is feeling the strain of America’s growing need for long-term care.

How Americans Pay for Long-Term Care

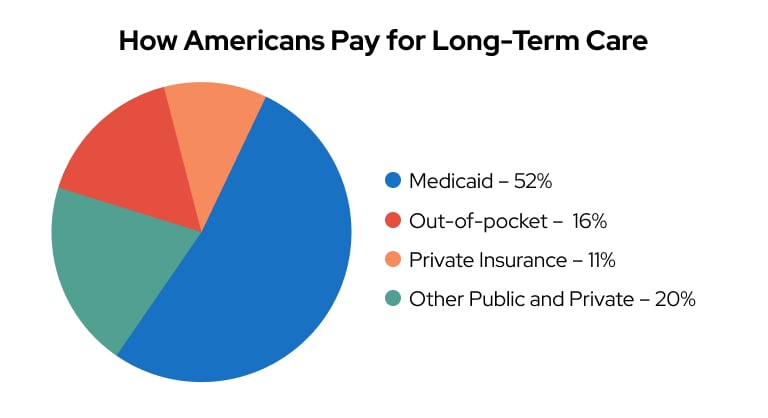

Americans spent $379 billion on long-term care in 2018, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Care in a nursing home or assisted living facility can cost hundreds of dollars a day.

Right now, Medicaid pays for more than half of long-term care in the United States. Private insurance and out-of-pocket payments pay for another quarter. The rest comes from other sources, including veterans benefits.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

About 11 million people on Medicare are also enrolled in Medicaid — something called dual eligibility. But to enroll in Medicaid, you have to have limited income and resources.

The Medicare population is expected to grow by 30 percent between now and 2036, according to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Health Forum. The authors expect that there will be increased pressure on Medicaid to step in and help with long-term care.

They point out that Medicaid eligibility and enrollment standards have changed little in the past 30 years. And they warn that without reforms, Medicare enrollees even slightly above the poverty level will face skyrocketing out-of-pocket costs for long-term care.

COVID-19 Pandemic Stretched Nursing Homes to the Limit

The COVID-19 pandemic hit nursing homes hard — more than 184,000 COVID-19 deaths in the United States happened in nursing homes, where residents were most vulnerable to the virus’ most serious complications and where the coronavirus could quickly spread in the pandemic’s early days.

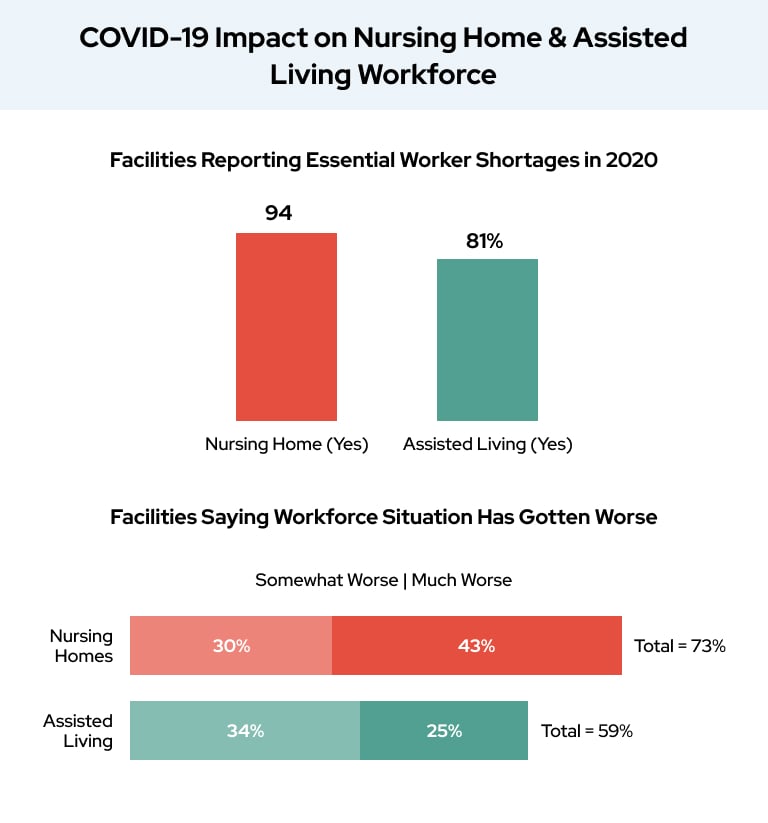

COVID-19 also took a toll on staffing at nursing home and assisted living facilities, according to a survey from the American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living (AHCA/NCAL).

“The survey results clearly indicate that the long-term care workforce is facing serious challenges, and our country must make significant investments to help address these shortfalls,” Mark Parkinson, AHCA/NCAL President and CEO said in a statement.

During 2020, the survey found widespread shortages of licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, dietary staff and housekeeping at a majority of nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

Even as COVID-19 cases decreased in 2021, more than 25 percent of nursing homes still reported staffing shortages as of June 2021, according to AARP.

Parkinson says state and federal lawmakers need to commit to “significant investments” to deal with staff shortages.

“This begins with addressing chronic underfunding of Medicaid for nursing homes, which currently only covers 70 to 80 percent of the cost of care,” Parkinson said.

Advocates Push Ideas to Fix “Broken” Long-Term Care System

Long-term care advocates have put forward plans they claim will strengthen America’s long-term care system and help Americans pay for this care as they age. Most of these plans call for changes to Medicaid.

AHCA/NCAL has put out a Medicaid reform plan it calls the “Care for Our Seniors Act.” It calls for increasing federal Medicaid funds to the states, creating a standardized national framework for “reasonable costs” for long-term care, and modernizing Medicaid rates to match current costs then make sure they rise with the pace of inflation.

The authors of the July 2021 JAMA Health Forum article claim that Medicaid enrollment is unnecessarily complicated. They recommend automatically enrolling people in Medicaid if they show up on some other means-tested program such as SNAP — or Food Stamps — benefits.

AARP calls the pandemic and the White House’s focus on long-term care a dual opportunity to open a conversation about the “fractured and outdated system of long-term care” in the United States.

Reimagining long-term care in America should involve support and services that not only improve care facilities but give people more options — such as more opportunities to receive care at home — according to Nancy LeaMond, AARP’s chief advocacy and engagement officer.

Long-Term Care Reform Chances After the Infrastructure Compromise

The White House plan calls for beefing up Medicaid to address long-term care.

Originally part of President Biden’s infrastructure plan, the proposed $400 billion Medicaid expansion was removed as part of bipartisan compromise talks. It is expected to live on as part of a separate spending plan.

While advocacy groups are targeting ideas that they want to see included in any plan the White House presents to Congress, retirement planners also advocate that younger Americans start planning now for the possibility of having to shoulder out-of-pocket costs for much of their own long-term care.

Medigap or Medicare Advantage plans can help with health care costs when you retire. But they may leave you with high out-of-pocket costs for nursing home or assisted living stays.

It’s estimated that more than half of all Americans will require long-term care by the time they turn 90. And almost half of that group will be responsible for some of the cost of that care when they need it.

Your web browser is no longer supported by Microsoft. Update your browser for more security, speed and compatibility.

If you need help pricing and building your medicare plan, call us at 844-572-0696